Signed in as:

filler@godaddy.com

Signed in as:

filler@godaddy.com

"Beat poet, Kabbalistic scholar, and Lower East Side legend, Lionel Ziprin, and his wife and principal collaborator, Joanne Ziprin. In 1950, Joanne Eashe—a dancer, illustrator, and model—married poet and Kabbalah scholar Lionel Ziprin. Their union was a pivotal moment in the underground history of the Lower East Side, a neighborhood aptly described by poet Janine Pommy Vega as “the meeting place of Old World mysticism and New World craziness.” Lionel Ziprin, born and raised in the LES, would become one of its most hallowed cultural figures. However, it was his wife Joanne who, in the early 1950s, claimed the couple’s stake in the booming post-War economy, infiltrating that last bastion of good, old fashioned, American incorruptibility: the holiday greeting card.

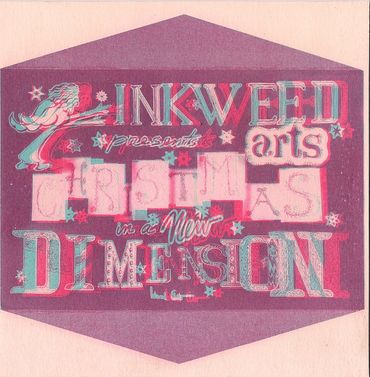

Founded in 1951, Inkweed Studios occupied a loft at 128 Lexington Avenue. The couple set out to create handcrafted, personalized “studio” cards, drawing on Joanne’s illustrative talents and Lionel’s hermetic, proto-Beat wit. Their cards aimed to rival those mass produced by the Hallmark Company, which had a virtual monopoly on the business at the time. In a letter from 1953 addressed to potential investors, Joanne and Lionel state that Inkweed has “worked hard to design, perfect and market an idea in greeting cards that we believe in. . . having to do with imagination, bits of black magic and shoe strings, which all too few people accept in lieu of cold, hard, cash.”

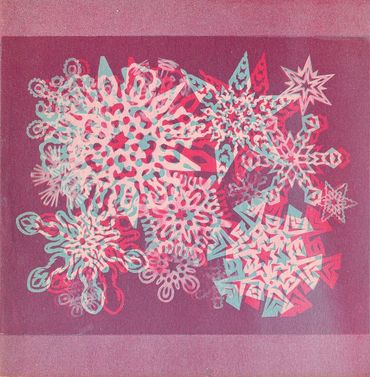

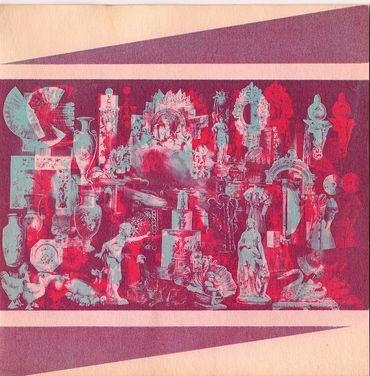

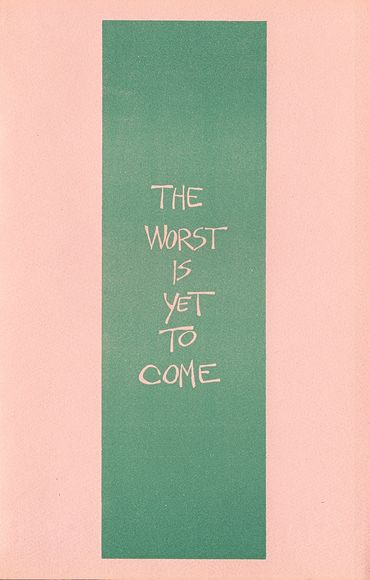

Inkweed offered itself as a launching pad for a handful of equally ambitious and talented artists, several of whom found their first paying commercial jobs with the company. These include polymath artists Harry Smith and Jordan Belson, painter and filmmaker Bruce Conner, and illustrators Barbara Remington and William Mohr. Smith’s instantly recognizable geometric designs were used for a series of hand screened Christmas cards, which echoed the artist’s famed series of drawings and collotypes inspired by Kabbalistic themes. Their most prodigious collaborator, however, was Conner, who met the Ziprins on a visit to New York in 1951. While studying art at Wichita University and the University of Nebraska, Conner regularly sent The Ziprins card concepts, alongside completed linoleum cuts and meticulous printing instructions. Conner’s work for the Ziprins—inspired by the two-dimensional, alien forms of painter Paul Klee and the absurdum ad infinitum ethos of Dada and Beat—infused Inkweed with a heavy dose of subversive wit and black humor. Conner’s vision inspired the Ziprins to take greater risk in their own designs, expanding the parameters of what the company could and would soon become.

Within a year Inkweed offered a full line of three-dimensional, screen-print cards (sold together, for $.50, with Inkweed 3D glasses) and intricate, hand-colored, three-panel foldouts. A national distribution deal helped Inkweed get their cards into department stores (including B. Altman & Co.), gift shops, and college bookstores. By 1954, however, the company’s high production costs and ramshackle accounting would bring it to the brink of bankruptcy. The Ziprins were forced to sell their share in Inkweed to stationer Fred Mann and Co. Mann managed the affairs of Inkweed for a few more years, cheaply rehashing several of its designs and concepts, much to the chagrin of its artists.

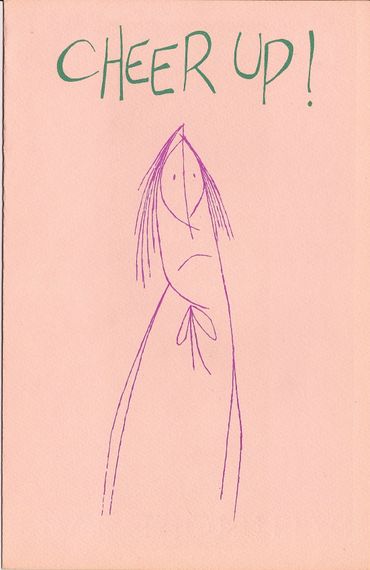

During this period of transition, the Ziprins conceived of another commercial venture. In early 1955, from the ashes of Inkweed Studios, The Haunted Inkbottle was born. Continuing to produce personalized, high-quality greeting cards, the Ziprins sought to expand their reach by manufacturing finely printed books and ephemera. Working out of a new studio at 6 East 17th Street, the couple again recruited the talents of Conner, Remington, and Mohr. Remington would go on to design several notable book covers for Ballantine, and Mohr’s comically menacing, Edward Gorey inspired figures became a fixture of The Haunted Inkbottle aesthetic. To a far greater degree than its predecessor, Inkbottle maintained itself as a self-sustaining entity. For nearly five years it enjoyed a steady stream of business and returning clientele. The Haunted Inkbottle, however, never quite reached its goal of expanding into new media—though, as the company archive reveals, this was not due to any lack of will. Literally hundreds of Inkbottle drawings, ink blocks, and sketches exist for unpublished books and other waylaid projects, such as silk screen reproductions of Piet Mondrian paintings and an elaborately designed set of tarot cards.

Spanning the years 1951 – 1959, From Inkweed to Haunted Ink provides a unique window into one of the most curious and wonderfully cracked attempts at merging Beat sensibility with American consumerism. Additionally, the exhibition brings into relief the significant contributions of Joanne Ziprin—a rare and pioneering female artist and entrepreneur, who in an era dominated by strong, male, personalities, made an indelible, largely unprecedented mark on the fabled history of the Lower East Side in the 1950s and 60s.'"

© 2023 Lionel Ziprin Estate | All Rights Reserved